How I Created and Manage This Website

I’ve previously received a questions asking for advice on how to create a website like mine, and in order to help others looking to make blog sites or portfolios like this, I thought I’d give a full technical breakdown of how this website works, including web design, hosting, domain management, and lastly, article writing. Beware: to make a website like this, you will need to be comfortable with both the heavy technical aspects of running a site like this alongside the creative aspects of producing this content. The biggest pro to this website is that the vast majority of this website (and all of its core functions) are completely free to produce, run, and manage, but there are several bells and whistles that I willingly fork up about 30 USD yearly to operate, and I’ll explain why shortly.

Hosting

This website is hosted through GitHub Pages, which is an entirely-free static website hosting service that operatures through hosting out of GitHub repositories. All you need to do to make a basic github pages site is to first make a GitHub account and then follow the instructions on the GitHub Pages landing page to produce the minimal github pages example, which will be hosted at (your github username).github.io. This domain is provided free-of-charge by GitHub, but I didn’t quite like it (mufaro3.github.io), so I switched to a custom domain (see “Domain Management”).

It’s a simple process to get set-up, and all you really need to understand for this section is how to make a github repository named correctly (to auto-integrate github pages), and then from there, the rest is web design.

Web Design (Programming)

Now, remember how I said that this site is a static site. That means that it’s contents are (mostly) non-dymanic, meaning that there is no database attached to this website in any way. Dynamic elements of the site are website contents that aren’t directly attributed to the site contents and can change regularly without manually changing the site, and this site does contain some dynamic elements such as the youtube videos, user comments, and a (soon-to-be) mailing-list, but these elements are all embedded from other services.

In the case of this site, all of the page contents are generated from special text files known as Markdown using Jekyll, a popular static site generator written in the programming language Ruby. The main advantage of this is that all of the posts on the site are very easily and concisely written in Markdown then compiled out into the HTML that you view on your web browser. Most importantly, due to Jekyll’s popularity, it has a quick-and-easy integration for GitHub pages, not requiring any compilation to occur locally (although, I obviously could just compile the site locally and have GitHub pages serve the compiled form).

Theming

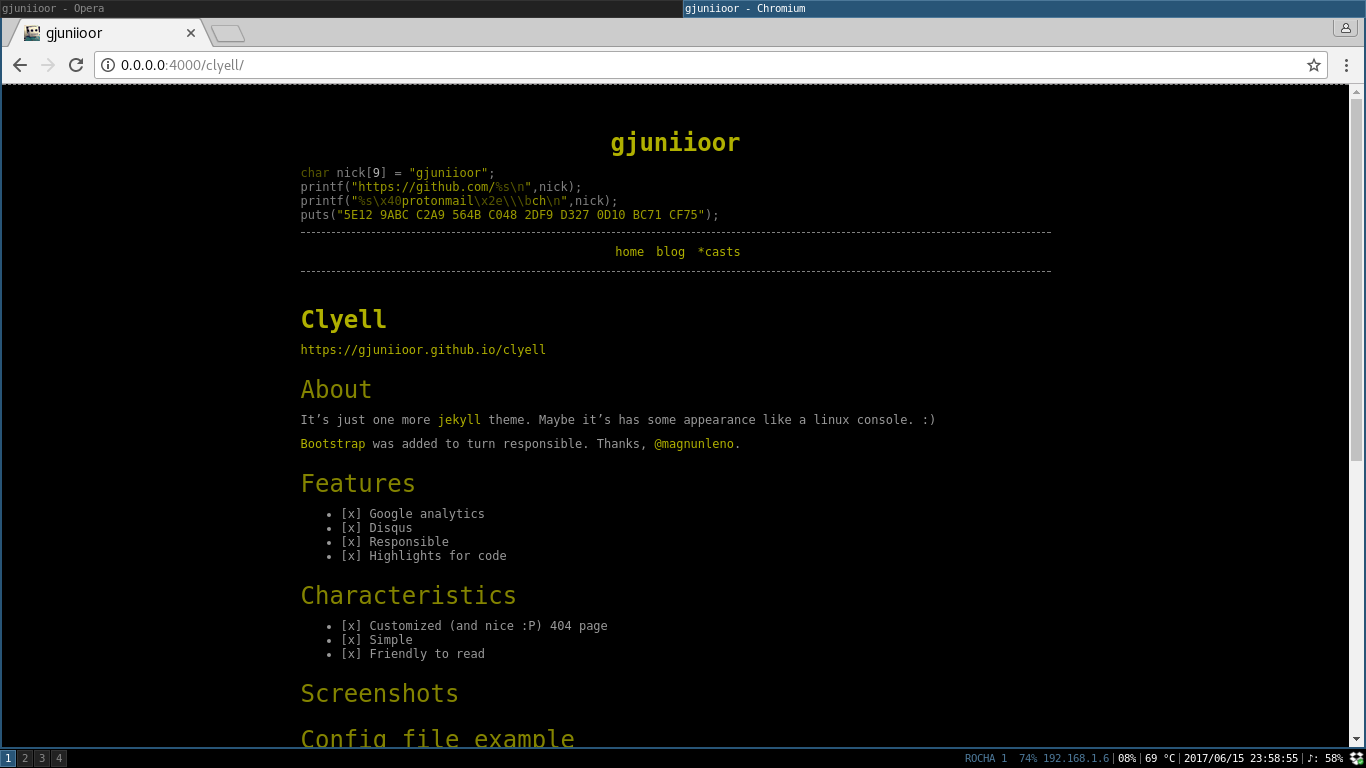

For theming on Jekyll, I started by taking a theme that already exists, Gildasio’s Clyell, and started adapting it manually. There are many Jekyll tutorials available online, so I’m not going to get into the specifics for how each element of this website was adapted from Clyell (there is a lot), but to give a general summary, I cleaned up and standardized the theming system of main.css, moved all of the syntax highlighting parts of main.css out and introduced a different theme (gruvbox), and removed bootstrap (the css library). If you don’t understand basic HTML/CSS, most of what I just said won’t make sense, but similarly, any further tweaking to the layout of the webpage won’t really make sense if you don’t understand HTML and CSS, so if you wish to make a blog website like this without learning those things, just download a premade theme from a website like Jekyll Themes and don’t make any changes.

Domain Management

GitHub Pages automatically provides a domain for all websites it hosts, the aforementioned <username>.github.io, but I didn’t really like this domain (plus, I wanted a cool custom e-mail address), so I purchased a custom domain from NameCheap for about 15 USD a year alongside another 15 USD a year for one custom email address for a total of 30 USD a year for everything. From there, all I needed to do was configure the GitHub Pages site to automatically force any users that connect to the website to connect via my domain by setting the domain of the website on the repository settings, and while there, I also set the website to automatically enforce HTTPS over HTTP (so all traffic to/from this website is automatically encrypted).

Article Writing

The Technical Part

Posts have to be stored under _posts in a very specific way, that being

YYYY-MM-DD-<post-link>.md

and each post requires a header like

---

layout: post

title: "a look into a quantum mechanical carnot engine (alongside a bit of python)"

date: 2025-07-24 12:19:00

comments: true

categories:

- programming

tags:

- physics

- python

- mathematics

---So, to automate this, I have a bash script under _posts labelled newpost.sh. Let’s say, for example, that I wanted to write a new post on the basics of number theory. I would first cd into the _posts directory then call newpost.sh:

$ cd ./_posts/

$ ./newpost.sh number-theory-basicsLet’s say that the current time as of running that command was January 10th, 2026, at 12:37 PM (48 seconds in, or 12:37:48). The script would therefore know to generate the file _posts/2026-01-10-number-theory-basics.md storing

layout: post

title: "number-theory-basics"

date: 2026-01-10 12:37:48

comments: true

categories:

- category

tags:

- tag

---and from there, I would open the file with emacs with

$ emacs -nw ./2026-01-10-number-theory-basics.mdand just edit in the title and tags and the category to produce something like

layout: post

title: "An Explanation of the Basics of Number Theory"

date: 2026-01-10 12:37:48

comments: true

categories:

- programming

tags:

- mathematics

---Keep in mind that “programming” doesn’t mean that it’s an article about programming, it just means that it will end up on the “programming”/STEM board that I call lambda.

From there, I just write the post content normally in Markdown on Emacs. Once I’m done writing, I add the new file to the git working tree with git add

$ git add ./2026-01-10-number-theory-basics.mdand then commit that file alongside any other changes I made with a short comment about what changed

$ git commit . -m 'basics of number theory article'and lastly, I push the article to the main branch.

$ git pushThis is a considerably easier process with editors like Visual Studio Code that have simpler, non-terminal Git integration, but I don’t have a problem with doing it all manually via terminal and editing with Emacs. I like it this way.

The Artistic/Motivational Part

Lastly, for the motivational part, I keep a small notepad with me where I write down ideas whenever I get them (such as short questions that bug me) and then I settle them by sitting down and writing an article. Like they say, a man that’s thinking all the time will have nothing to think about but thoughts, so the best way to think about things worth writing about is to not think about things worth writing about, but instead, go out and live your life for a while and then things will come to you, and when they do, save those ideas somewhere.

Most of the things that I have written about thus far are projects that I worked on for fun months prior without ever intending to really do a full write-up, but afterward, I thought it would be useful to write a description of what happened, what worked, what didn’t, and what I learned. For any creators or experimenters out there, I think that format is really worth a try.

It’s incredibly easy to avoid writer’s block when you aren’t trying to force ideas out of you. Some ideas just come naturally, and when they do, you need to listen. Those are the ideas most worth writing down. It always seems like they come at the dumbest times, like when you’re taking a bath or going for a walk or brushing your teeth or some shit, but ironically, those mundane moments where you’re just existing in monotony are the best for thinking because your brain understands just how meaningless that time is. I think that meaningless time really has all the time in the world for that exact reason. Spend more of your life actually living it than thinking or writing and then think and write as much as you can.

If you like my posts, feel free to subscribe to my RSS Feed.