Implementing Eliza in Lisp

Historical Context and Explanation

On January 1st of 1966, Dr. Joseph Weizenbaum of MIT published the following revolutionary paper to the Association of Computing Machinery’s (ACM) communications journal, where in it, he describes a new program designed to simulate natural human conversation called Eliza [1].

Eliza was a revolution. He based the program on a Rogerian psychotherapist due to the nature of conversational style Eliza employs, with much of Eliza’s conversation simply being saying what the user says back to them (after performing some conversions). Consider the following example exchange (taken directly from Weizenbaum’s paper), where Eliza is in all caps and the user speaks normally:

Men are all alike.

IN WHAT WAY

They're always bugging us about something or other.

CAN YOU THINK OF A SPECIFIC EXAMPLE

Well, my boyfriend made me come here.

YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

He says I'm depressed much of the time.

I AM SORRY TO HEAR YOU ARE DEPRESSED

It's true. I am unhappy.

DO YOU THINK COMING HERE WILL HELP YOU NOT TO BE UNHAPPY

I need some help, that much seems certain.

WHAT WOULD IT MEAN TO YOU IF YOU GOT SOME HELP

Perhaps I could learn to get along with my mother.

TELL ME MORE ABOUT YOUR FAMILY

My mother takes care of me.

WHO ELSE IN YOUR FAMILY TAKES CARE OF YOU

My father.

YOUR FATHER

You are like my father in some ways.

WHAT RESEMBLANCE DO YOU SEE

You are not very aggressive but I think you don't want me to notice that.

WHAT MAKES YOU THINK I AM NOT VERY AGGRESSIVE

You don't argue with me.

WHY DO YOU THINK I DON'T ARGUE WITH YOU

You are afraid of me.

DOES IT PLEASE YOU TO BELIEVE THAT I AM AFRAID OF YOU

My father is afraid of everybody.

WHAT ELSE COMES TO MIND WHEN YOU THINK OF YOUR FATHER

Bullies.

DOES THAT HAVE ANYTHING TO DO WITH THE FACT THAT YOUR BOYFRIEND MADE YOU COME HERE

Some keys things to notice is Eliza’s ability to maintain a memory context of things the user says, such as seemingly being able to understand the fact that the user is sad, has a complex relationship with her father, and that her boyfriend made her come here (to Eliza’s therapy). Consequently, these understandings require understandings of their own, such as requiring Eliza to have enough context to understand what a boyfriend is, what a father is, what it means to be sad (and the fact that this is a negative emotion), and even what therapy is, and this tree of context for all pieces of information in natural human language can get very, very large, going all the way down to base principles. Such understandings are becoming more common today with the emergence of large language models (LLMs), but for a program run on a room-sized mainframe computer in the 1960s, before the language C was even invented, such luxuries were completely impossible. Therefore, that begs the question: just how the hell did Weizenbaum make this all possible?

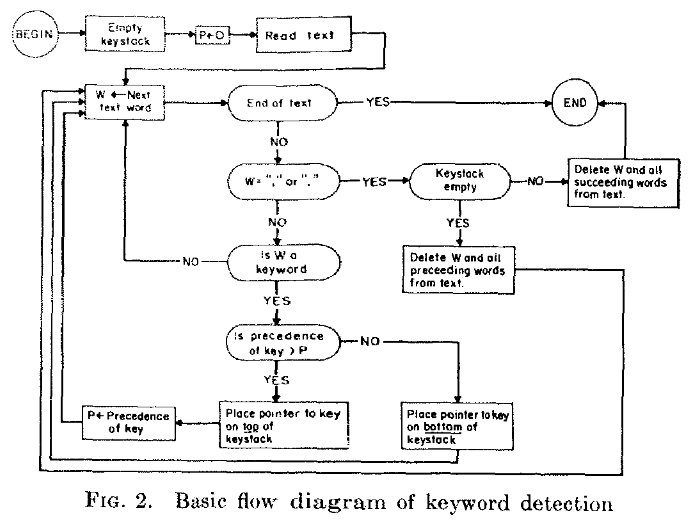

This is a flowchart describing how Eliza works from the original paper.

Well, that’s the trick of it. Eliza doesn’t understand anything at all. Weizenbaum essentially designed Eliza to work like a kind of programmable dictionary, where he manually specified in a series of patterns dictating how the program both analyses user speech (decomposition rules) and produces new speech (reconstruction rules). In a sense, these patterns could be said to essentially just be the program taking what a user says, breaking it down into core parts, recognizing the general structure of the sentence based on the sentence fragments it broke the sentence down into, then filling in a stencil for a response sentence based on this structure to say back to the user (like an Ad-lib).

Take this other example conversation (also from the paper) to understand this:

It seems that you hate me.

What Eliza would do is look through a ranked/ordered list of keywords in order by decreasing priority until it finds a keyword that matches the sentence (if none are found, it would use a catch-all, which will be explained later). For this sentence, it would likely match “you,” which often indicates that the user is making a statement about Eliza. From there, the pattern it might choose could be

0 YOU 0 ME

which essentially says to capture two wildcard tokens and two hardcoded word tokens:

- all of the words before “you”

- “you”

- all of the words between “you” and “me”

- “me”

where the number represents the number of words to capture. The order of these tokens is also important, and the number in which the token appears can be used to reference it later. Now for this original sentence, we decompose it into the following tokens:

- It seems that

- you

- hate

- me,

and then we can apply a reconstruction rule associated with the decomposition rule like

WHAT MAKES YOU THINK I 3 YOU

and the 3 represents the index of the token to insert into the sentence, which would be “hate” (and would be stylized to all-caps for printing out). Thus, this makes the sentence

WHAT MAKES YOU THINK I HATE YOU

and this is what is printed to the user.

What is important to understand from this example is just how Eliza masquerades intelligence, a system Weizenbaum refers to as “minimal context.” If I had just shown the interaction without explaining what occured as

It seems that you hate me.

WHAT MAKES YOU THINK I HATE YOU

then it would have been very easy to assume that Eliza would be required to understand the meaning of the word hate or what it means to hate as an emotion. However, this was not necessary whatsoever. Eliza doesn’t understand context like emotions or people or even the meanings of words in any way whatsoever. This is why I refer to Eliza like a programmable dictionary. Eliza acts like a collection of these decomposition and reconstruction rules (with a few more tricks built in) to mimick having this context as much as possible without actually having it.

Implementing My Own Eliza

Like I said previously, Eliza was written well before the C language (but likely would not have been written in C even if C had existed at the time). Rather, Eliza was written in MAD-Slip, Weizenbaum’s personal creation list processing programming language similar to John McCarthy’s Lisp.

So, naturally, I’ve sought to try and recreate Weizenbaum’s Eliza in Common Lisp (which is quite different from both languages, but that’s okay). I started with the following rules to use as examples:

(defparameter *reflections*

'(("i" . "you")

("am" . "are")

("my" . "your")

("me" . "you")

("you" . "me")

("your" . "my")))

(defparameter *raw-rules*

(list

(cons "0 YOU 1 ME"

(list

"What makes you think I 2 you?"

"Do you genuinely believe that I 2 you, or do you simply wish that I 2 you."))

(cons "*"

(list

"Please tell me more."

"Interesting... continue.."))))All it contains are some rules for reflecting directed language (like switching you to me and me to you) and the previous literature example we explained before alongside some catch-all phrases to default to when nothing else can be said.

I also would need the ability to keep counters on each of the reconstruction rules for how much they have been used, so I made the following rule initialization function

(defun initialize-rules (raw-rules)

"Transform (string . (responses)) to (string . ((response . 0)))"

(mapcar (lambda (rule)

(destructuring-bind (pattern . responses) rule

(cons pattern

(mapcar (lambda (r) (cons r 0)) responses))))

raw-rules))From there, I started on the program’s starting point:

(defun main ()

(eliza-say "Hello. My name is Eliza, and I'll be your therapist today. How are you feeling?")

(loop (format t "~%YOU: ")

(let ((input (string-downcase (read-line))))

;; formatting just so the conversation looks nice

(next-line)

;; take randomly between 1-3 seconds to respond to feel

;; more natural

(sleep (random 3))

(when (is-farewell input)

(eliza-say (eliza-farewell))

(return))

(eliza-say (generate-response input)))))All next-line does is print a newline character and is-farewell simply checks for if the user stated a goodbye or other kind of program-ending statement. Otherwise, it loops continuously on processing the user input and generating a response with generate-response.

The response generation function looks like

(defun generate-response (input)

(loop for (decomp . reconsts) in *rules*

do (multiple-value-bind (matches? tokens)

(apply-decomposition (car decomp) (reflect input))

(when matches?

(let ((reconst (alexandria:extremum reconsts #'< :key #'cdr)))

(rplacd reconst (1+ (cdr reconst)))

(return (apply-reconstruction reconst tokens))))))

(randitem (cdr (assoc "*" *rules*))))and, essentially, what it does is for any input, it loops through Eliza’s ruleset in order (the natural order of the rules doubles as being its match order, and I chose to just rawly try mating decomposition rules rather than performing a keyword search as the performance upgrade from keyword matching was not necessary for the ruleset size) and selects the first decomposition rule that matches the sentence.

It performs this search by simply trying to apply decomposition rules to obtain decomposed tokens

(apply-decomposition (car decomp) (reflect input))

Once this rule is found (when matches?), it locates the first-order reconstruction rule with the lowest number of uses

(reconst (alexandria:extremum reconsts #'< :key #'cdr))

then it proceeds to increment the useage conuter for this reconstruction rule

(reconst (alexandria:extremum reconsts #'< :key #'cdr))

then lastly applies the reconstruction rule given the tokens we previously obtained from the decomposition rule and returns that result:

(return (apply-reconstruction reconst tokens))

So, that was simple enough! Now we just need to program in the apply-decomposition and apply-reconstruction functions, and the program is good-to-go. Unfortunately, this is the hard part. The sketch of apply-decomposition that I completed looks like

(defun apply-decomposition (decomp sentence)

(multiple-value-bind (match captures)

(cl-ppcre:scan-to-strings (decomp->regex decomp) sentence)

(cons (not (null captures)) captures)))What this function does is essentially acts as a wrapper for cl-ppcre:scan-to-strings, first converting the decomposition rule to a regular expression using decomp->regex and then applying scan-to-strings and producing a cons pair containing both a boolean value of whether or not the match was successful and the list of tokens that the regular expression captured.

Naturally, this function is fine, but the issue lies in the function for converting decomposition rules into regular expressions to actually pattern match on them.

(defparameter *max-tokens* 10)

(defun decomp->regex (decomp)

"Converts a decomposition rule to a regular expression"

(let ((tokens (cl-ppcre:split "\\s+" decomp))

(regex-parts '()))

(loop for token in tokens

do (if (cl-ppcre:scan "^\\d$" token)

(let* ((n (parse-integer token))

(regex-group (format nil "((?:\\w+\\s+){0,~D}\\w+)"

(if (or (> n *max-tokens*) (= 0 n))

*max-tokens* n))))

(push regex-group regex-parts))

(push token regex-parts)))

(join-strings (nreverse regex-parts) "\\s+")))This function has been the bane of my entire life. I hate it, and I’m starting to believe that it hates me. This function has been designed to attempt to convert decomposition rules from Weizenbaum’s syntax into regular expressions that can tokenize sentences that are applied to the rule based on group matching, but this is, in fact, incredibly difficult to do.

First, what it does is split the decomposition rule along whitespace, then it loops through each of these tokens and checks if the token is a number (indicating the number of words to match). Every time it isn’t a number, it just pushes it onto the list of regular expression parts, regex-parts, and if it is a number, if parses the value into an integer and then builds a regular expression to try and capture that many words (up to *max-words*) and pushes that regular expression onto regex-parts. Once it has gone through the entire set of tokens, it joins all of the parts in regex-parts with a whitespace matcher then returns that as a regular expression.

Naturally, all of that is fine except for the hardest part, making a regular expressing for matching \(n\) words in a sentence given an integer. I tried to write that with

(n (parse-integer token))

(regex-group

(format nil "((?:\\w+\\s+){0,~D}\\w+)"

(if (or (> n *max-tokens*) (= 0 n)) *max-tokens* n)))

however, for the life of me, I could not get this to work. I think my regular expressions knowledge is garbage (or worse than garbage), particularly the regular expression string "((?:\\w+\\s+){0,~D}\\w+)". I could never manage to figure out just how to write the kind of regular expression I was trying to make here, one capable of handling the entirety of words.

The next problem on the list was writing apply-reconstruction. I wrote the following:

(defun apply-reconstruction (reconst tokens)

(let ((reconst-tokens (cl-ppcre:split "\\s+" reconst))

(sentence-parts '()))

(loop for token in reconst-tokens

do (if (cl-ppcre:scan "^\\d$" token)

(let ((index (1- (parse-integer token))))

(push (nth index tokens) sentence-parts))

(push token sentence-parts)))

(join-strings (nreverse sentence-parts) " ")))and what this does is similar to the process for converting decomposition strings to regular expressions. It starts by splitting the reconstruction rule on whitespace into tokens and building a stack of sentence fragments called sentence-parts. Then, it loops on these tokens and adds any nonnumeric tokens directly back onto sentence-parts, and once it finds a token that is an integer, it parses it and then uses the number to index the tokens that were obtained from the decomposition of the user’s sentence originally and pushes that value onto sentence-parts. Lastly, it concatenates all of these sentence parts together into one string with spaces between each token, and then this is returned back to the user. As this function is much more straightforward, it’s seemed to work a lot better than apply-decomposition.

So, this is where I’m at. I wish I could come and tell you all that I successfully made an Eliza implementation in Common Lisp, but all I got was a bunch of functions that manages to get close to something working simply because I don’t understand regular expressions for the life of me. It’s been fun, though. I’ve learned quite a bit about programming in Lisp and the early days of artificial intelligence (as the field of artificial intelligence in its early days is where Lisp made its introduction and solidified itself into the history of computer science).

[1] “ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine” by Joseph Weizenbaum. Link

If you like my posts, feel free to subscribe to my RSS Feed.